Work stealing Fork Join Parallel Framework in C++

(Jiarui LI (jiaruil2), Xin JIN (xinj2))

URL

https://cmu15618-project-team-jiaruil2-xinj2.github.io/website/

Summary

We are going to implement a fork-join parallel framework with work-stealing distributed queues in C++. Also, we would like to analyze its performance, overhead, and bottleneck under different implementation strategies, such as a child or continuation stealing, lock-free queue, etc.

Background

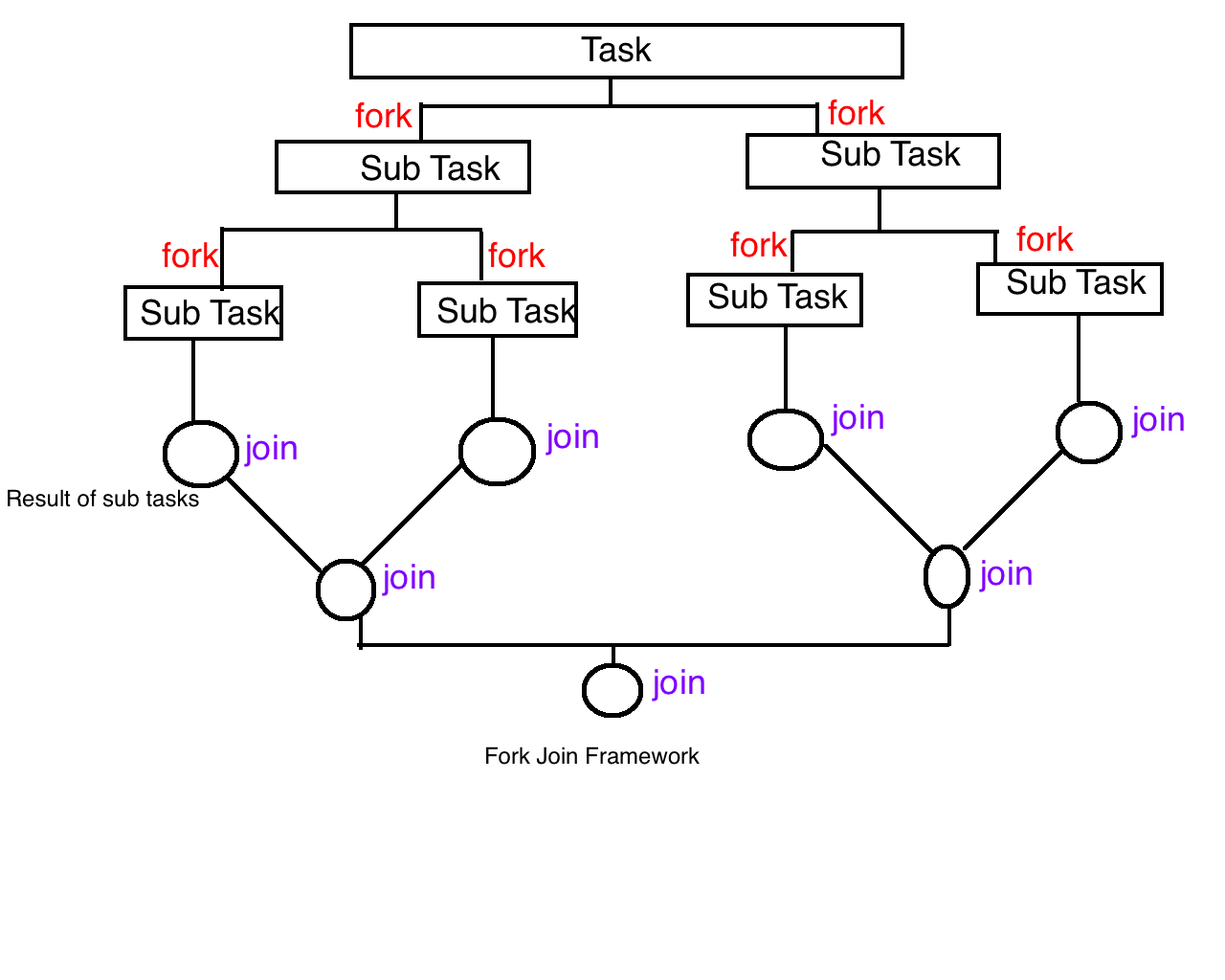

The fork-join model is a simple and efficient approach to executing parallel programs. This parallel pattern allocates threads and dynamically divides tasks recursively until every task reaches a certain granularity. All the threads execute their own tasks parallelly without block except to wait out subtasks. Threads will join at some subsequent points to continue sequential execution.

Problems that suffer a heavy workload of computing and can easily be divided into several subtasks can benefit from this easy-to-use parallel scheme. Similar to divide-and-conquer algorithms, divided tasks are computed on multiple cores. Without too much overhead, programs can be sped up at a significant level.

(https://self-learning-java-tutorial.blogspot.com/2015/07/java-fork-join-framework.html)

(https://self-learning-java-tutorial.blogspot.com/2015/07/java-fork-join-framework.html)

The challenge

Implementing a fork-join framework is challenging for the following reasons. For one thing, in order to get the expected speedup, the scheduling cost should be as small as possible. There are a lot of possible implementation strategies with their own tradeoffs. For instance, the number of works a thread should steal when its own work queue becomes idle is a key design problem. In addition, the implementation of the work queue also has lots of possibilities, such as a single centralized queue or per-thread distributed queues with coarse/fine-grained locks or even lock-free synchronization. For another, from the users’ perspective, a simple and easy-to-use API is also important. Doing this project, we want to learn the internal mechanism of fork-join parallel paradigms, explore different implementation strategies and analyze their pros and cons.

Workload: Using the fork-join paradigm, tasks may block to wait for the completion of their subtasks. Therefore, there are dependencies between threads executing parent tasks and sub-tasks. However, since the task abstraction is separated from the execution instances, and we tend to use a dynamic assignment along with a work-stealing strategy, it is less likely to have divergent execution.

Constraints: Using the fork-join paradigm, because of the nature of dynamic task generation, it is hard to anticipate the workload of each task and impractical to statically map each task to each parallelization instance. Therefore, a distributed work queue with a work-stealing strategy is a better solution in our opinion.

Resources

Although we will start from scratch, we have found some good paper to begin with which discusses how this parallel design pattern works in detail.

- R. D. Blumofe and C. E. Leiserson, “Scheduling multithreaded computations by work stealing,” Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 1994, pp. 356-368, doi: 10.1109/SFCS.1994.365680.

- Färnstrand, Linus. “Parallelization in Rust with fork-join and friends: Creating the fork-join framework.” (2015).

- Frigo, Matteo & Leiserson, Charles & Randall, Keith. (1999). The Implementation of the Cilk-5 Multithreaded Language. ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 33. 10.1145/277650.277725.

- Lea, Doug. (2000). A Java Fork/Join Framework. ACM 2000 Java Grande Conference. 10.1145/337449.337465.

Goals and deliverables

PLAN TO ACHIEVE

We plan to implement a framework that can be used for the fork-join parallel paradigm. The framework is expected to allocate threads using a thread pool to execute tasks. Also, we want to try two implementation strategies which are child stealing and continuation stealing. On one hand, we will apply this model to a simple problem like merge sort to analyze the performance and speedup under different numbers of processors compared with a simple sequential version of the program. On the other hand, we would like to achieve the results using different strategies, break down the time spent in the execution and discuss the overall performance.

HOPE TO ACHIEVE

If time permits, we would like to build an auxiliary visualization tool to demonstrate the working process and the scheduling graph of the fork-join model.

Besides, we would like to explore the different granularity of parallelism. To be specific, we want to try using processes, threads, and user-level threads as workers.

In addition, we would like to construct a distributed fork-join framework and get rid of the limitation of one single machine. For the demo, we decided to show the plots of speedup compared to the performance on a single processor to demonstrate the effectiveness of our fork-join model. Running the program to show the output result is also a good way to demonstrate the correctness of our framework. If we finish the visualization tool we hope to achieve, we can use it to generate a gif that can be more intuitive to see the process of the fork-join model. Further, we hope to learn more about the advantages and disadvantages of this parallel model when dealing with different amounts of workloads and different numbers of processors.

Platform choice

We would like to implement this framework in C++ 11. In addition, we plan to test our framework on GHC machines and PSC machines. Since GHC machines are free and have eight cores, they will be a good place for us to do benchmarking and initial testing on speedup. We also hope to see the performance with a larger number of cores, because we want to know if there is a bottleneck or other factors which limit the speedup. This is one of our focuses in this project, and that’s why we choose PSC to do some final testing.

Results and Analysis

We used the computing resources in the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Cluster (PSC) to evalute our implementation. To be specific, we use the non-shared nodes in the cluster, which are equipped with two AMD EPYC 7742 processors (2.25-3.40 GHz, 2x64 cores), 256 GB RAM and 256MB L3 cache.

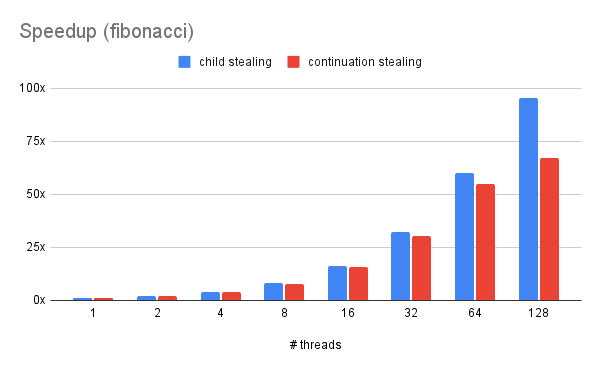

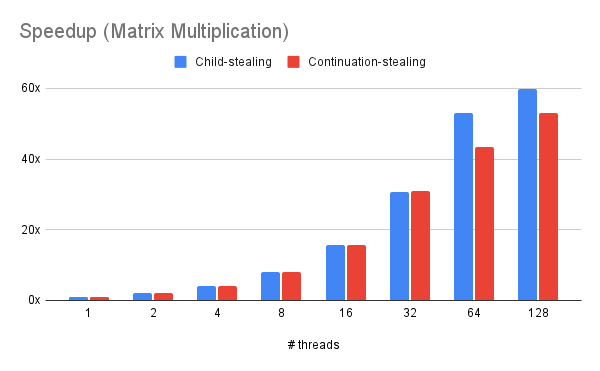

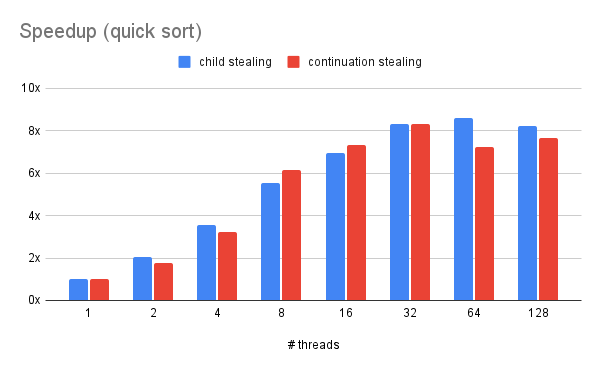

We mainly used our framework to accelerate three typical applications. First is to recursively calculate the 50th term of the Fibonacci sequence, with the sequential calculation threshold equals to 30. Second is matrix multiplication. For simplicity, we tested our model with 2 2048x2048 identity matrix with granularity of 64x64. Third is to use quick sort to order 1,000,000,000 integers with the sequential calculation threshold equals to 1,000,000. We ran both the child-stealing policy and the our 2Q implementation on these applications in the cluster.

Task Granularity

In the problem of the Fibonacci sequence, we started with a small task granularity. That is when a task is under a user-defined threshold, that task can no longer be divided, and we work on that task directly instead of dividing it into smaller pieces. In this case, the threshold of task granularity is the input number. However, we found the performance was not good as we expected since we distributed more work to worker threads. Eventually, we increased the granularity to achieve good performance on this task. The benchmark started with 50, and the threshold was 30. The program was sped up linearly with the number of threads growing up before the number of threads got to 64 for both two stealing policies. Although we allocated more threads in our thread pool, the program was not accelerated to an ideal speed, especially for the continuation-stealing. Though the speed actually increased, it still struggled when we increased the number of threads from 64 to 128. In this case, child-stealing performed better compared to continuation-stealing.

Stealing Granularity

On one hand, we believe that we may not get a great threshold value for this problem. Because in our previous testing, the threshold value actually mattered the overall speed. As we mentioned earlier, a bad threshold can lead to bad speed which could be worse than the sequential program. On other hand, more contention in continuation-stealing can be one factor. In child stealing, the stealing granularity is always a task. However, in continuation-stealing, the stealing granularity is a continuation that has less workload than a single task for most of the time. Since, in our design, every work queue except the thread 0’s work queue is empty at the start of the process. So, stealing can happen at an early stage of the whole process. A small stealing granularity may lead to more contention potentially in our design.

Trade-off Between Task Granularity and Contention

Task granularity is an important concept in our design with the divide-and-conquer algorithm because it can affect greatly the contention. From our point of view, the reason why a small task granularity resulted in bad performance is that numerous contentions were dragging down the speed. Considering a scenario that the task granularity is very small, this actually is good for workload balancing since the workload is distributed in a find-grained way. However, the work queue of workers can be empty very soon, since they finish their work faster compared with a large task granularity. In other words, stealing happens more frequently. Although we have semi-lockfree work queues for workers, we still have entry locks for stealing. Numerous contentions for acquiring entry locks can be a great cost in this case. However, considering task granularity is a little bit out of our scope, since task granularity is complicated and different for different applications, and we only provide a framework for users.

Schedule

- Week 1: Literature review, API design + Thread pool

- Week 2: Dedicated Distributed Queue

- Week 3: work stealing I (intermediate checkpoint)

- Week 4(a): lock-free queue optimization using dequeues as work queue

- Week 4(b): implementation of continuation stealing policy (single work queue)

- Week 5(a): implementation of continuation stealing policy (distributed work queue)

- Week 5(b): implementation of sorting using fork-join model

- Week 5(c): implementation of matrix multiplication using fork-join model

- Week 6(a): use case analysis

- Week 6(b): finalize our design

- Week 6(c): write the final report

- Week 6(d): prepare for the poster session